Richard's Restoration: Kelly Laymon Revisits 'The Woods Are Dark'

By, Derek Clendening

For horror authors and readers alike, the late Richard Laymon was the friendly face behind some of the grittiest and most visceral novels of his day. Authors who came to prominence after 2001 often hear fond recollections of a good-natured man with a penchant for literary gore. New readers have relied on reprints of his earlier work, which splatter the same level of bloodshed today as they did back when they were originally published.

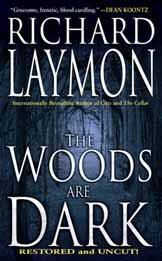

American readers often missed out on Laymon’s work, since many first editions weren’t readily available here in the U.S. until he inked a deal with Leisure books in the 90’s. The years following his untimely death saw the re-release of many of his titles, including Savage and The Midnight Tour. Also reprinted were his first two novels published by Warner books, The Cellar and The Woods Are Dark. Similar to Charles Dickens’ unfinished final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, an air of mystery surrounds The Woods Are Dark. While the novel was completed and published, the Warner version was a far cry from Laymon’s vision. More than fifty pages were cut out at the publisher’s insistence, as if to water down the novel’s intensity. Such cuts have left devout Laymon readers with a sense of incompletion. Dickens himself had many a faithful reader who sought to finish Edwin Drood’s tale. Certainly someone could return The Woods Are Dark to the gory glory that Laymon had envisioned in 1981. His 28-year old daughter Kelly knew that restoring the novel would be challenging, but she was more than ready to take on a daunting task.

American readers often missed out on Laymon’s work, since many first editions weren’t readily available here in the U.S. until he inked a deal with Leisure books in the 90’s. The years following his untimely death saw the re-release of many of his titles, including Savage and The Midnight Tour. Also reprinted were his first two novels published by Warner books, The Cellar and The Woods Are Dark. Similar to Charles Dickens’ unfinished final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, an air of mystery surrounds The Woods Are Dark. While the novel was completed and published, the Warner version was a far cry from Laymon’s vision. More than fifty pages were cut out at the publisher’s insistence, as if to water down the novel’s intensity. Such cuts have left devout Laymon readers with a sense of incompletion. Dickens himself had many a faithful reader who sought to finish Edwin Drood’s tale. Certainly someone could return The Woods Are Dark to the gory glory that Laymon had envisioned in 1981. His 28-year old daughter Kelly knew that restoring the novel would be challenging, but she was more than ready to take on a daunting task.

When Dark Scribe Magazine caught up with Kelly Laymon, we were eager to find out what motivated her to tackle such an enormous undertaking. We were keen to learn more about the process, the challenges, and the triumphs of restoring her late father’s work.

Stroll into a secondhand bookstore, and there’s an excellent chance that you might find a dog-eared, yellowing copy of The Woods Are Dark in the bargain bin. The tenacious collector might even be lucky enough to find a copy in pristine condition. Sure, beholding the green-foiled cover means taking a trip in the way-way-back machine, but horror was a different business than it is today. Likewise, the publishing business has seen its share of wrinkles. Even the modes of writing a novel have changed thanks to modern technology. Outlining these points is significant in understanding the young Laymon’s journey.

Laymon began her endeavor with three boxes of manuscripts, notes, and paper - not to mention the work ahead of her. Though The Woods Are Dark was her father’s only novel to need restoration, it was not the first restored novel that Leisure has published. Jack Ketchum shares almost an identical experience with his first and second novels Off Season and She Wakes, the former published the same year as Laymon’s novel. One could argue that publishers were caught off guard by the blossoming splatterpunk era, forcing editors to keep their red pens handy.

“Ketchum and my father led very parallel lives with respect to their dealings with publishers in the 1980s,” Laymon says,  adding, “They bonded over many similar experiences.” She remarks how much she enjoyed Ketchum’s forward in Off Season, since the experience was so close to her father’s. Both were hard-working young writers, hoping to make it big, but who also fell into some traps. In his afterward to Off Season, Ketchum explains that he was so happy to have his novel published that doing rewrites was hardly an issue. He simply gave in to the publisher’s demands. In her father’s non-fiction book, A Writer’s Tale, Richard Laymon confirms that he was young and excited and gave in to the publisher’s demands in order to see his work in print.

adding, “They bonded over many similar experiences.” She remarks how much she enjoyed Ketchum’s forward in Off Season, since the experience was so close to her father’s. Both were hard-working young writers, hoping to make it big, but who also fell into some traps. In his afterward to Off Season, Ketchum explains that he was so happy to have his novel published that doing rewrites was hardly an issue. He simply gave in to the publisher’s demands. In her father’s non-fiction book, A Writer’s Tale, Richard Laymon confirms that he was young and excited and gave in to the publisher’s demands in order to see his work in print.

Readers and aspiring writers generally understand that a finished novel may vary slightly from the manuscript that the author turned in. Laymon notes that if you compare most of her father’s manuscripts to the finished products, you will find very little variance. But The Woods Are Dark was an entirely different story, as the changes were significant. The plot itself took a knock due to the fifty pages that were excised. The domino effect meant that entire subplots and themes were lost.

In Ketchum’s case, he had the chance to restore his own novel, so his new version would be in keeping with the plots that he’d envisioned. Further, he knew where all the pieces fit and could reconstruct the novel properly. Laymon, on the other hand, didn’t have that luxury. Luckily, her father was well-organized and left behind sets of manuscripts and notes in perfect order. “He kept everything. And he kept things well organized. Which is very helpful now,” she says.

Still, Laymon says she could rely on her vivid recollection of her father’s remarks whenever the discussion arose.

“I was always aware of what was going on in his career,” she says. “When the topic of The Woods Are Dark would come up either privately, at signings or cons, on message boards or during panel discussions, he would talk at great length about what a mess the whole thing was.” She adds that “The story of The Woods Are Dark is pretty well known among his diehard fans. In the introduction to the revised version, I discuss, in greater detail, what exactly transpired.”

Restoring the novel had been in the back of Kelly’s mind for a number of years, and she’d engaged in more than a little banter with Leisure’s senior editor, Don D’Auria, about making it a reality. But Laymon needed the restoration to press beyond cocktail conversation and come to fruition, so once she had the green light, she took her father’s meticulously organized notes and manuscripts and set to work.

The process of restoring someone else’s novel can be a creative process in and of itself. Plots need to be restructured and gaps need to be filled. For Laymon, settling on a method for the restoration of the novel was vital. Further, decisions on how to piece together the various drafts needed to be made. First, she decided which manuscripts to use and what notes were the most relevant. Next, she had to match her data with the plots and themes of the published book.

“I had three or four different drafts to sort through, Laymon explains. “Since we’re talking about a book written almost thirty years ago, there was even a handwritten draft. I found a chunk of typewritten pages that consisted of deleted portions, which were published in a chapbook a few years back.”

She further explains that the process was more than just re-adding the missing scenes. After all, this job meant re-introducing storylines that never made it into the original book. “I found a chunk of pages containing the surrounding storyline,” she says, “and the two chunks fit together perfectly. The page numbers lined up and the story made sense.”

Tackling such a task can be likened to following a roadmap that’s missing a corner, or worse, the final destination. Or it can as frustrating as finishing a jigsaw puzzle with a few pieces missing. Still, Laymon traveled down that road with an admirable sense of confidence. “Oddly enough,” she says, “it turned out to be much easier than I was expecting. Especially considering that my father said in print that the novel could never be put back together again. Once I sat down and took a good close look at things, it became pretty clear.”

Up next was deciding by what means she would produce the final manuscript for Leisure. “For the sake of production,” she explains, “I typeset the book myself to send to Leisure. That turned out to be the most time-consuming task. I’m a fast typist, but I also double-checked each page against the manuscript as I went along.”

For Laymon, the restoration was not a matter of starting at page one and trying to repair every last nuance from the outset. According to her, the discrepancies in the manuscript didn’t occur until her dad really cranked up the heat. “The first seven chapters are the same in both editions,” she says, “and then things change in a pretty big way. The deleted chapters amount to almost fifty pages worth of new material. However, to be true to the original manuscript, an almost equal portion of the formerly published version is not there. The explanation made great sense to this Dark Scribe interviewer, since the slim restored version seems no thicker despite the additional fifty pages. As Laymon explains it, “Storylines are dropped. Storylines are added. It all works out.”

In restoring a novel, one might think that even well-organized manuscripts and notes would leave some gaps. In such a case, the person restoring the novel would need to use their imagination about how certain situations panned out. When DSM asked Laymon if this happened to her, she says, “I was definitely hoping that I wouldn’t have to do that. If it had come to that point, I’m not sure what I would have done. Luckily, I never had to cross that bridge.”

As for motivation and support, Laymon certainly had the writing community to rely on. She and her mother, Anne, still attend the World Horror Convention and Necon, and have kept in regular touch with many of her father’s writing pals. She also knew that she could depend on her mother for help if she found herself in a pinch. Though she says she’d wanted to restore the novel for five years, she never thought that she would be able to pull it off.

“I don’t think Mom ever thought I could pull it off either,” Laymon says. “I had looked through the boxes a lot and had a pretty good idea of what I had to work with, but it was a long time before I sat down and really got working on it.” She mentions that though genre friends and authors didn’t physically aid the restoration process, their support and encouragement meant a great deal to her. “My mother and genre friends were all hoping that the finished product would work out. Everyone was very supportive and enthusiastic.”

According to Laymon, Leisure’s involvement in the restoration process was somewhat limited. Certainly, they showed a great deal of confidence in her ability to ‘do the impossible’ and granted her free reign to handle the restoration as she saw fit. When asked if Leisure required anything more from her, she says, “Since I had been talking about doing it for years, Don D’Auria was very aware of my intentions. The deal was that when The Woods Are Dark rolled around in the contract, they would let me know and that I would start working on it.”

The Woods Are Dark, along with Ketchum’s Off Season and even Stephen King’s The Stand, are examples of how heavily publishers can influence one’s reading experience. It’s food for thought for anyone browsing through the paperback rack at Rite Aid or Wal-Mart. With the grunt work finished and the restored book published, Laymon needs only to wait on how the book will be received. For hardcore Laymon fans, the unedited version promises to be a treat. And for those readers who are new to Laymon’s work, they will have their first crack at The Woods Are Dark the way it was meant to be read. In the end, they might even wonder what all the initial fuss was about and why the late dark scribe was forced to make the drastic cuts. Laymon says that although she hopes the book will be well-received, the process itself has offered a strong measure of satisfaction.

The Woods Are Dark, along with Ketchum’s Off Season and even Stephen King’s The Stand, are examples of how heavily publishers can influence one’s reading experience. It’s food for thought for anyone browsing through the paperback rack at Rite Aid or Wal-Mart. With the grunt work finished and the restored book published, Laymon needs only to wait on how the book will be received. For hardcore Laymon fans, the unedited version promises to be a treat. And for those readers who are new to Laymon’s work, they will have their first crack at The Woods Are Dark the way it was meant to be read. In the end, they might even wonder what all the initial fuss was about and why the late dark scribe was forced to make the drastic cuts. Laymon says that although she hopes the book will be well-received, the process itself has offered a strong measure of satisfaction.

“So far, the feedback has been positive,” she says. “I really hope readers will enjoy it.”

Purchase your copy of the restored and uncut version of Richard Laymon’s The Woods Are Dark.

Reader Comments