In-Depth Discussions with Today's Darkest Talents

D. Harlan Wilson: Keeping It Irreal

By, Blu Gilliand

D. Harlan Wilson is an award-winning short story writer and novelist. He is also a cultural theorist, an English professor, editor-in-chief of The Dream People, and practitioner of such literary sub-genres as critifiction, scikungfi, and irrealism. He’s a former casino dealer, town crier, sommelier, and garbage man.

D. Harlan Wilson is an award-winning short story writer and novelist. He is also a cultural theorist, an English professor, editor-in-chief of The Dream People, and practitioner of such literary sub-genres as critifiction, scikungfi, and irrealism. He’s a former casino dealer, town crier, sommelier, and garbage man.

In other words, D. Harlan Wilson is a hard man to pin down. But while he and his writing may avoid pigeonholing like the plague, there’s no doubt that he’s got some very interesting things to day – both in his fiction and in the interview that follows.

Dark Scribe Magazine: You’ve earned two Masters degrees (English and Science Fiction Studies) and a Ph.D. in English. How has this education fed into your craft?

D. Harlan Wilson: Immensely. All of my novel-length works are critifictions, i.e., they can function both as fiction and scholarly criticism, depending upon the angles of incidence from which readers approach them. Without my background in the critical study of literature, I would have never become a creative writer. I was a graduate student for about ten years and my focus in school was on reading and interpreting literature. I always wrote fiction on the side, though, and inevitably one informed the other. They continue to do so. Now more than ever, in fact.

By merging theory and fiction, part of my goal is to construct narratives that can be enjoyed for story, characterization, etc., but that also prompt readers to think about society, culture, technology, the meaning of life, and shit like that. Criticism can be so dry. And fiction can be so bland and formulaic and predictable. I try to spruce things up by combining and accessorizing the two forms.

We live in a wildly apathetic world. If somebody’s head blowing up in a creative way piques a reader, good. If somebody double-takes a potential theoretical assertion about, say, the ways technology has reconfigured desire and the body, great. I try to get people’s attention. I try to push the boundaries of narrative, of what is expected from narrative. The problem is getting people to pick up a book. Most people don’t read, or if they do read, it’s a book assigned to them in college, or a book they get because they liked the movie it was based on. That’s cool. I have no lofty aspirations to convert the masses. In the words of Alex from A Clockwork Orange, “I do what I do because I like to do what I do.” But I can’t deny that I wish the Written Word was held in higher regard than it is nowadays.

Dark Scribe: Which is more important in your work? Style or plot and characterization? If you put one over the other, why?

D. Harlan Wilson: I consider myself a stylist more than anything — I try to be a stylist anyway. In other interviews I have said that I don’t care about plot or character, i.e., I don’t focus on it, and that’s true to some degree. But you can’t tell a story without plot or character, of course—these things are essential to fiction—whereas style isn’t. There’s so much crummy prose. And that’s fine. Generally speaking, readers don’t care about prose. They care about whether or not they can empathize with characters and the degree to which a story engages them. So I think I just take plot and character for granted. Stylizing prose, on the other hand, is a chore and I pay a lot more conscious attention to it.

Dark Scribe: What goals do you have for your work? Are you writing to entertain or challenge your readers, or do you write for yourself without trying to generate a particular reaction or feeling in the reader?

D. Harlan Wilson: I try to do all of those things. I try to both educate and entertain readers as much as myself. It’s hard for me to really get into a book or story. Not because I’m a literary snob or anything. My tastes are just very particular. I like dark humor, above all, but executed in certain ways. And I like science fiction and horror and fantasy, but not genre speculative fiction, generally speaking, as there are numerous genre works that I enjoy and revere. Thing is, there’s billions of books out there. So much to choose from. I find myself tapping into the billions, trying out authors and books that I haven’t read, and coming up disappointed, or at least unfulfilled. I want to like more literature. But I don’t! Then again, unlike my wife, who can read purely for pleasure — I find that difficult to do. When I read, I’m always thinking about how I might use or reappropriate or extrapolate aspects of this or that narrative for my own creative or scholarly pursuits. That’s bad, I think. I wish I could just sit down for an hour or two and get lost in a novel. I used to be able to do that. But graduate school ruined me.

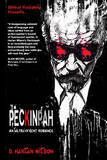

As for inciting particular reactions or feelings in readers, I do make an effort, but much of what I write is ultraviolent, for creative and critical purposes, and I’m honestly desensitized to a lot of the grue that I depict. Not always, though. For example, there’s a chapter in my upcoming novella, Peckinpah: An Ultraviolent Romance, where two women torture a man. The first version of the chapter depicted two men torturing a woman, and it really disturbed me — and my wife! — so I switched gender roles. My own disgust wasn’t the final catalyst; there were aesthetic reasons for the alteration relating to the nature of patriarchy and misogyny. Point is, it’s one of just a few instances in which my writing has struck an emotional chord with me. For the most part it doesn’t. I’m mainly preoccupied with how my narratives function in their totality, as word-portraits of extrapolated realities, with or without violence, sex, etc. But sex and violence are at the core of the human condition; they’re difficult to avoid. Some of my readers might be grossed out or taken aback. But I don’t think I portray things that are beyond the scope of what most intelligent adults can relate to on some level.

Dark Scribe: You’ve published both flash fiction and long form — which is more challenging to write? Which — if either — is more rewarding?

D. Harlan Wilson: Flash fiction is easier — much easier. A piece of flash fiction can simply capitalize on one idea or image or string of words. Writing a novel is much more of an intellectual, psychological and emotional investment, if only because of the length (my flash fiction ranges from 10-500 words whereas most of my novels are around 40,000 words). But with length comes more ideas, characters, plotlines, histories, relationships, etc., all of which need to be closely tracked and kept in order during the writing process. It’s a pain in the ass. I enjoy writing flash fiction more; I can compose a story with a beginning, middle and end in one sitting and be done with it. Novels take me anywhere from six months to a year. I have to record notes all the time, and I’m thinking about the goddamn novel all the time, and I’m annoyed by dreams about the novel, and I’m constantly bouncing ideas off of my wife, and so on. But despite this imaginative vigilance and obsession, it’s massively rewarding in the end. There’s nothing like finishing and polishing a book you’ve written that you really like, even if it’s just for the time being (in retrospect, I don’t like most of my writing and want to revise it, as is the case with many authors).

Dark Scribe: Irrealism? Bizarro? Do you like all these labels that get applied to your work, or would you prefer not to be labeled in any way?

D. Harlan Wilson: I like the term irreal — it is the most accurate term for my work. It’s somewhat complicated, but basically irrealism depicts absurdist, dreamlike, but generally recognizable worlds in which the cause and effect schema that you and I are subject to is either slightly or egregiously off-kilter.

D. Harlan Wilson: I like the term irreal — it is the most accurate term for my work. It’s somewhat complicated, but basically irrealism depicts absurdist, dreamlike, but generally recognizable worlds in which the cause and effect schema that you and I are subject to is either slightly or egregiously off-kilter.

I tend to merge irreal aesthetics with the speculative genres. It’s not surrealism—that’s different, although there are similar traits. Surrealism is more akin to Bizarro insofar as both were created as marketing tools and represented a wide range of artistry. Bizarro is an umbrella term for different kinds of fiction. Irrealism is one kind. Others include esoteric subcategories like “Tweeker Lit,” “Avant Punk” and “Subterficial Fiction.” But there are more familiar and straight-shooting forms like satire, minimalism and absurdism. These terms have all been conceived of by individual authors or their publishers to define their Bizarro styles.

Like I said, the idea is to sell books, and in this capacity Bizarro works; over the last 5 years it has really grown in popularity. That said, ultimately I don’t care what people call my writing. I’m not trying to write in a Bizarro vein. It’s nice to be able to say I write this or I write that, I guess. It’s convenient, anyway. The compulsion to categorize things is a basic human trait that I struggle with. I don’t like categories, but I recognize their use-value.

Dark Scribe: What’s the relationship of your work to horror? One and the same? Companions? Kissin’ cousins?

D. Harlan Wilson: Definitely not one and the same — if, that is, we’re talking about genre horror à la Stephen King, Dean Koontz, etc. I wouldn’t call them companions either. Kissin’ cousins is accurate enough.

Objectively speaking, if you look at, for instance, my novel Blankety Blank: A Memoir of Vulgaria and Koontz’s Intensity, there are fundamental similarities. Both novels feature a serial killer. Both contain fair shares of violence against the body. Both elicit fear and contain gross-out moments. And so forth. But our styles differ significantly. I tell stories with schizophrenic rigor; structurally all of my novels are fractal, and I perceive them as mosaics, portraits of the interaction of conscious and unconscious realms. Koontz’s style is more straightforward. I like reading both kinds of narration. I just prefer writing more experimental stuff and trying new things.

Objectively speaking, if you look at, for instance, my novel Blankety Blank: A Memoir of Vulgaria and Koontz’s Intensity, there are fundamental similarities. Both novels feature a serial killer. Both contain fair shares of violence against the body. Both elicit fear and contain gross-out moments. And so forth. But our styles differ significantly. I tell stories with schizophrenic rigor; structurally all of my novels are fractal, and I perceive them as mosaics, portraits of the interaction of conscious and unconscious realms. Koontz’s style is more straightforward. I like reading both kinds of narration. I just prefer writing more experimental stuff and trying new things.

It’s tough, though. I don’t want to write experimental prose that looks experimental simply for the sake of it, as you see in a lot of authors fashioned by MFA degrees. I want my narrative structure to reflect the actual content of my work. You might say I want my narrative to be a character as much as the characters the narrative illustrates.

Dark Scribe: Tell us about the online journal you edit, The Dream People.

D. Harlan Wilson: I’ve been the editor-in-chief for this journal since 2006. It used to be run by the publishers of Raw Dog Screaming Press, and before that by Carlton Mellick III, figurehead of the Bizarro movement and founder of Eraserhead Press. The RDSP folks got too swamped with book publishing and they were going to abandon The Dream People, so I offered to take over.

The Dream People primarily publishes irreal fiction — hence the subtitle “a journal of irreal texts.” We consider fiction between 5-1000 words, preferably around 500 words. There are also book reviews, interviews, artwork, microcriticism, novel excerpts, and comics and animation, although the latter two are harder to come by. Currently the journal is a biannual publication. I’d like to make it triannual, maybe even a quarterly, but I just don’t have enough time right now, and I probably won’t have time in the foreseeable future.

The journal caters to our increasing, Internet-spawned, collective short attention span. I don’t like to read long texts on a computer screen — I prefer to hold them in my hands and turn pages, and I know lots of readers who do, too. More importantly, The Dream People is a good advertising forum for both new and old authors and artists. The Internet is the best promotional tool for contemporary creative output; if nothing else, it permits authors and artists to reach large numbers of eyes quickly. I had a lot of help and encouragement when I started out writing from different people. The Dream People is one way I can give back. It becomes more and more important to me.

Dark Scribe: Tell us about your new book from Shroud Publishing, Peckinpah.

D. Harlan Wilson: Peckinpah is a 20,000 word novella in which I attempt to do several things. One is to represent the physical and psychological terrain of Midwestern American life. This is based on personal experience; I teach at a university in a small town called Celina in Ohio, although I relocated the state to Indiana in the book and called the town Dreamfield. So that’s the narrative space I inhabit. Within this space, I explore and critique some of the cinematic themes of filmmaker Sam Peckinpah, who has been called a forefather of ultraviolent aesthetics, an issue that concerns me both as a critical and creative writer. On one level, then, I express certain horrors of middle America and the ways in which I think this place sucks. On another level, I examine the great American romance with violence. That includes multiple forms of violence (e.g. cinematic, physical, psychological, cultural, narrational, technological, ecological, etc.).

Dark Scribe: How did Sam Peckinpah become a strong enough influence that you felt compelled to write a novel around him and his work?

D. Harlan Wilson: In addition to Peckinpah’s revolutionary and unprecedented use of violence in his films, I was interested in the man himself. I read a lot of biographical material on him when I was researching my book. He was a fascinating guy. He was this total fuckup. An alcoholic and a drug addict and a womanizer and a brawler. But there was a really soft and caring side to him, too. I like that sort of duality in people, or at least in characters I read or write about. I probably wouldn’t have liked Sam very much in person. I don’t like most artists I meet whose work I admire, whether they are filmmakers, actors, writers, or what have you: I have an idea of what they’ll be like and they consistently let me down. But that’s my problem, mostly.

It occurs to me that the moment I became intrigued by Sam Peckinpah was not after seeing one of his films but when my brother-in-law told me he committed suicide by stabbing himself, like, fifty times. It turned out not to be true — my brother-in-law had Sam confused with somebody else whose name I don’t recall. Some rock star, I think. Still, that’s what set the ball rolling for me.

Dark Scribe: What else do you have in the works?

D. Harlan Wilson: In addition to Peckinpah, I’m currently promoting two other books. One is a novel I mentioned before, Blankety Blank: A Memoir of Vulgaria, published earlier this year by Raw Dog Screaming Press. The other is a book of literary and cultural criticism, Technologized Desire: Selfhood & the Body in Postcapitalist Science Fiction, which debuted at the Science Fiction Research Association’s annual convention in June and was published by RDSP’s new nonfiction syndicate, Guide Dog Books.

Next year I have another novel coming out, Codename Prague, the second installment in my scikungfi trilogy, the first of which was Dr. Identity (or, Farewell to Plaquedemia). That one’s finished, more or less. Now I’m working on the third and final scikungfi novel, The Kyoto Man, which will be published in 2011.

Next year I have another novel coming out, Codename Prague, the second installment in my scikungfi trilogy, the first of which was Dr. Identity (or, Farewell to Plaquedemia). That one’s finished, more or less. Now I’m working on the third and final scikungfi novel, The Kyoto Man, which will be published in 2011.

As for criticism, I have been contracted to write a book on John Carpenter’s film They Live for Wallflower Press’s cultographies series. I’m only in the research stage of this project. It’s slated for release in 2012.

For more information on D. Harlan Wilson, visit his official author website.